Critical Connections: Visionary Organizing and Moving Beyond the Master’s Tools

Matt Birkhold

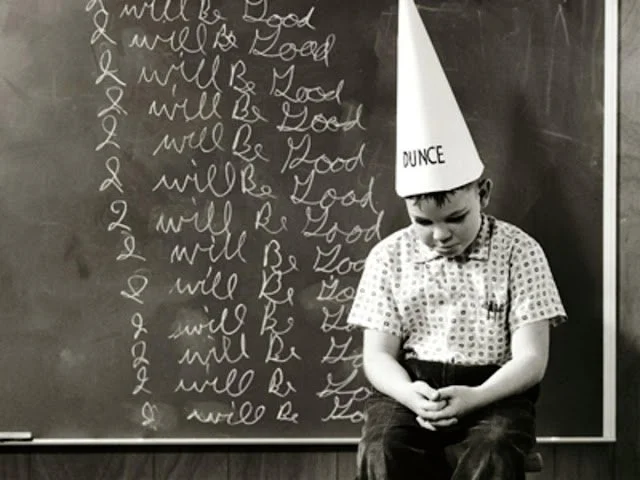

The first memorable lesson I learned about how to create change was in Ms Berry’s first grade classroom at Indian Prairie elementary school in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Myself and two other boys were washing our hands in the bathroom when Ms Berry came in, grabbed us, took us back to class, and wrote our names on the chalkboard. I have no memory of what we did or why she seemingly burst into the boys bathroom with such anger that I was frightened. But 38 years later I still remember her anger, sitting at my desk, and seeing my name on the board. I remember feeling scared. Humiliated. Would she call my mom? What other punishments might come my way?

I don’t remember what else happened that day but I know that Ms Berry’s anger and power over me changed my behavior that day. I also don’t think I ever got in trouble in her class again or ever fully trusted her again.

Force, control, and the ability to create fear are powerful tools for change. We often learn them in our families and in schools. Then, as adults we abide by them because fear of losing a job motivates us for social and financial reasons. I’ve never been physically forced to go to a job like I was forced to sit down by Ms Berry. Yet, the coercive power of an economy that makes my access to food and housing contingent on access to money feels similar to Ms. Berry’s direct force and power.

Because this kind of indirect force is so pervasive, even our attempts at social and organizational change often embody it. When we believe that only a critical mass of people can be the driver of change or be the prerequisite for change in a community or an organization, we are assuming that some group of people must be forced against their will to go along with other people’s ideas and/or agendas.

This belief that change requires critical masses is, to use a phrase coined by Audre Lorde, an example of what it looks like to use the master’s tools to create the change we want to see in the world. To further quote Lorde, the master’s tools, “may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

Beating the master at his own game is often necessary, but so is recognizing the limitations of winning his game. With these limitations in mind, Martin Luther King embraced critical connections in the course of struggle over desegregation because he saw that the force of critical masses would lead to the kind of bitterness that culminated with January 6, 2021. To create what Lorde called genuine rather than temporary change, we need tools for change that go beyond those of the master’s.

The components of Visionary Organizing are amongst these tools. It is capable of creating genuine, lasting change because it assumes that all people are capable of transforming and growing under the right conditions. Visionary Organizing nurtures critical connections and creates transformative conditions by using the tools of the collectively transformative components of Visionary Organizing: Imagining New Possibilities, Affirming Dignity, and Experimenting WIth Transformation.

Visionary Organizing offers a humanizing vision of what a community or organization can look like and attracts people to that vision by affirming their dignity rather than instituting an organizational change and implementing change management strategies or going into communities to educate, agitate, and organize. As a result, lasting change created by Visionary Organizing comes from experimenting with how people and groups transform rather than experimenting with how to control individuals and groups.

There are moments when a quick fix to a problem is necessary. In these situations, Visionary Organizing is not the right way to solve problems.

However, when a problem needs to be addressed at its root rather than at the level of symptoms, the collectively transformative components of Visionary Organizing allow us to solve problems by going beyond what’s possible with the master’s tools.